Art object as a scientific device

SCANNING MY MRI PHANTOMS

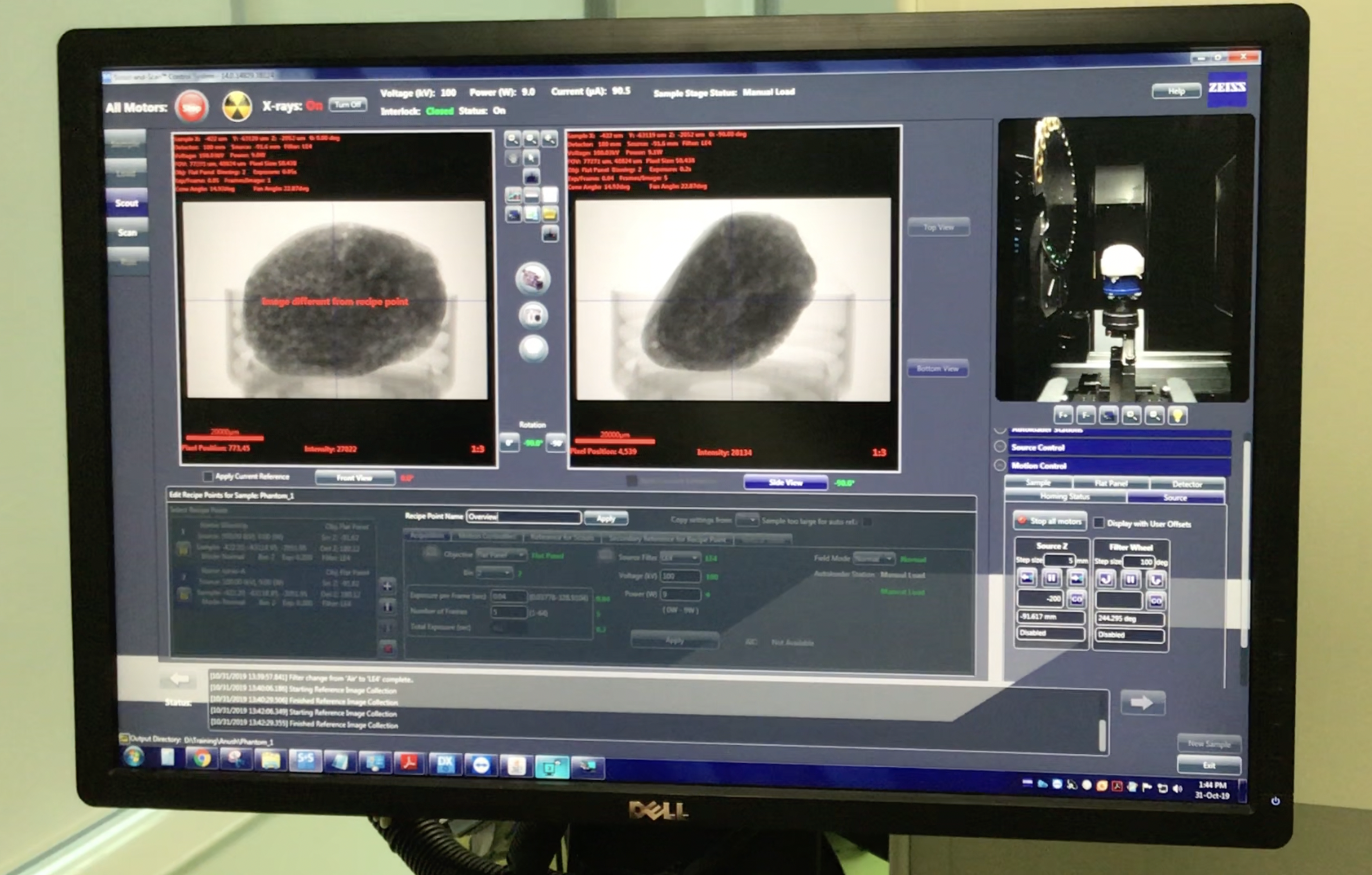

The process of scanning phantoms at The Francis Crick Institute and Future Technology Centre transformed my work from art objects into scientific specimens. Phantoms were prepared in line with laboratory protocols and my practice became both an artistic and scientific endeavour. Throughout 2019, early 2020, in autumn 2022, and Spring 2023 I scanned phantoms with Dr Bernard Siow: the MRI wizard at the Francis Crick Institute. Science-in-action merged into my creative work as Siow and I prepared the phantoms for the scanner in full PPE as required by laboratory protocol. We decontaminated the surface of my phantoms and sealed them in sterilised sealable plastic bags. After scanning they would be stored in a fridge in the lab along with other samples and specimens.In November 2019 I made a collection of phantoms to scan using CT at the Future Technology Centre (FTC) with Dr Anush Kolakalur. In these laboratories, I was able to ‘play scientist’ through an interruption of usual routines where my phantoms and I were “technocorporeal unit[s]” and non-standard laboratory subjects (Oslon, 2018, p. 120). I incorporated visits to the lab as part of my practice and interpreted ideas proposed by scientists as creative input.

LE / 1957

From The Immense Journey

An approach called ‘Assemblage Theory’ offers a way of doing practice-based research that benefits from charting, mapping and exploring the extent of practice and how it is entangled with materials, processes, spaces, communities and objects. These drawings map how TMMs are used and interact as if they were organs. The phantoms were scanned with Dr Bernard Siow at the MRI department of the Francis Crick Institute and at the Future Technology Center at Portsmouth to test reconstruction algorithms created by Dr Anush Kolakalur. Scanning as part of my artistic practice and used in scientific experiments was an interesting opportunity to bring scientific methods into the arts and apply a creative artefact to scientific studies.

Art object as a scientific device

In another experiment using my phantoms as scientific devices, I collaborated with Dr Anush Kolakalur on their PhD research by making bone density phantoms specifically to test CT reconstruction algorithms he had developed. The opportunity to collaborate and co-create and create phantoms for scientific research allowed me to briefly expand my phantom-making practice into another imaging modality (CT) which meant I could consider different kinds of material compositions using TMMs. I created bone-density phantoms using similar techniques developed for the MRI phantoms.

Their design was a question of matter and form resembling the spongy complexity of bone marrow rather than requiring that I create organs and systems within them. CT is used to measure bone density for diagnostic purposes. In 2020 and 2021 I had bone density scans to measure bone density loss resulting from treatment and to see if my cancer had spread. Dr Kolakalur had previously used bone sourced from a butcher but needed a model whose constituent materials could be isolated and scanned on their own.

Dr Kolakalurs doctoral thesis is called

NEW COMPUTATIONALLY EFFICIENT ITERATIVE RECONSTRUCTION (IR) ALGORITHMS FOR COMPUTATIONAL TOMOGRAPHY (CT) IMAGES

and can be found following this link. These phantoms more closely resembled biological forms: their fleshy appearance was uncanny and they reminded me of samples from the dissecting room. The scans took place around the time of my cancer diagnosis and the tan-pink colouring and shape of these phantoms were similar to the description of my tumour described in my pathology report. This was incredibly confronting, almost as if I had created facsimiles of my tumour. The feminist tenant of the personal is political and the affective turn became wrapped up with my feelings towards my phantoms as devices and my growing medical-technological dependency.