Re-Corporealising MRI Data_ a Practice-based investigation into MRI

INTRODUCTION

Corporeal matter as perceived by MRI straddles definitions of substance, organism, subject and object. MRI interacts with the body through nuclear magnetic resonance and electrodynamics, bringing us into contact with the body as a person, as an assemblage of biochemical reactions, as a patient and a cellular, molecular, atomic and subatomically composed entity.

This research project and exhibition use artistic processes as a method for investigating MRI and what it means to be a body as defined by MRI. The artworks exhibited were created as part of a process of interacting with the physics of MRI and making art objects as scientific devices.

MRI is a non-invasive biomedical imaging technology that visualises tissues within the body. MRI is an interesting piece of physics that interacts with the body. As a technology, it draws on the quantum mechanical properties embedded in corporeal matter - particularly hydrogen ions, also known as protons (H+). MRI brings together multiple aspects of our ontology. MRI interacts with the body through nuclear magnetic resonance and classical electrodynamics, and thus physics allows us to connect to the abject. This brings us into contact with the body as a person, a patient, a member of a community, and as a cellular, molecular, atomic and subatomically composed entity.

HOW MRI WORKS: Scientific Illustration as Method for Understanding

The magnetic field of an MRI penetrates our materiality and requires both quantum mechanics and classical electrodynamics to work. MRI involves the phenomena of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and the intrinsic subatomic properties of spin, angular momentum and magnetism possessed by atomic nuclei. Protons within atomic nuclei are like tiny spinning magnets. The first stage of MRI involves the powerful MRI magnet which aligns the spin of the protons, lining them up like synchronised swimmers. Following this alignment, the protons are energised with radio frequency electromagnetic energy (RF photons) in the form of high-frequency RF pulses. This causes them to resonate.

As the protons absorb the RF energy, they wobble away from the magnet’s alignment to varying degrees depending on what material or substance they are in. When the RF signal is turned off the protons still resonate. Refocusing the magnet re-aligns the protons, causing them to re-emit the difference in RF as the NMR signal.

The time it takes for the protons to emit the signal is called relaxation time; it generally comes in two kinds of measurement: T1 and T2. The difference in relaxation time and proton density are essential factors in creating accurate MRI images. When the NMR signal is emitted it is detected in the scanner. These signals are converted into a digital biomedical image using the mathematics of signal analysis including a type of maths called Fourier transforms (FTs). This process is computational and mathematical where the wave properties of the NMR signal are used to figure out what kinds of matter/molecules are resonating where.

The body and its substances, molecules and atoms interact with the MRI system (magnet, RF signals and sensors/detection mechanisms) at the ‘body machine interface’. This interface is beyond (or within) the boundary of the skin. The magnet and RF signals are able to work across multiple scales of magnitude. By thinking about MRI in this way I was able to create sculptures that interact with MRI as if it were a body. Making sculptures with the body-machine interface in mind made it possible for my work to intersect, interact and intra-act with MRI. The analogue NMR signal being converted/processed/computationally interpreted into a digital biomedical image is perceived as the analogue-digital interface in my research (a non-scientific term).

This project begins with MRI and MRI data. The sculptural, woven, drawn and painted work created as part of this practice-based body of research draws on the mathematical and physical processes of MRI. The artwork created makes use of scientific information and biomedical imaging laboratories as part of the creative practice. Works include sculptural ‘phantoms’ that are used to investigate the interface between body and machine in MRI and are named after scientific devices of the same name. By thinking about how matter interacts with MRI, I could make these artefacts from within and as part of MRI. My artistic phantoms are made using ‘tissue mimicking materials’ that from the perspective of the scanner, could be part of a living organism.

This body of work includes woven works, patterns and swatches created in response to the way in which an MRI scanner turns signals from the body into a digital image of the body. These woven works and the patterns developed for them are based on the mathematical processes of signal analysis. They were made from within and part of the MRI process. Drawings, illustrations, diagrams and paintings created as part of my research process are also created to chart my artistic practice's entanglements and constellational nature.

001a

001a 001b

001b 001c

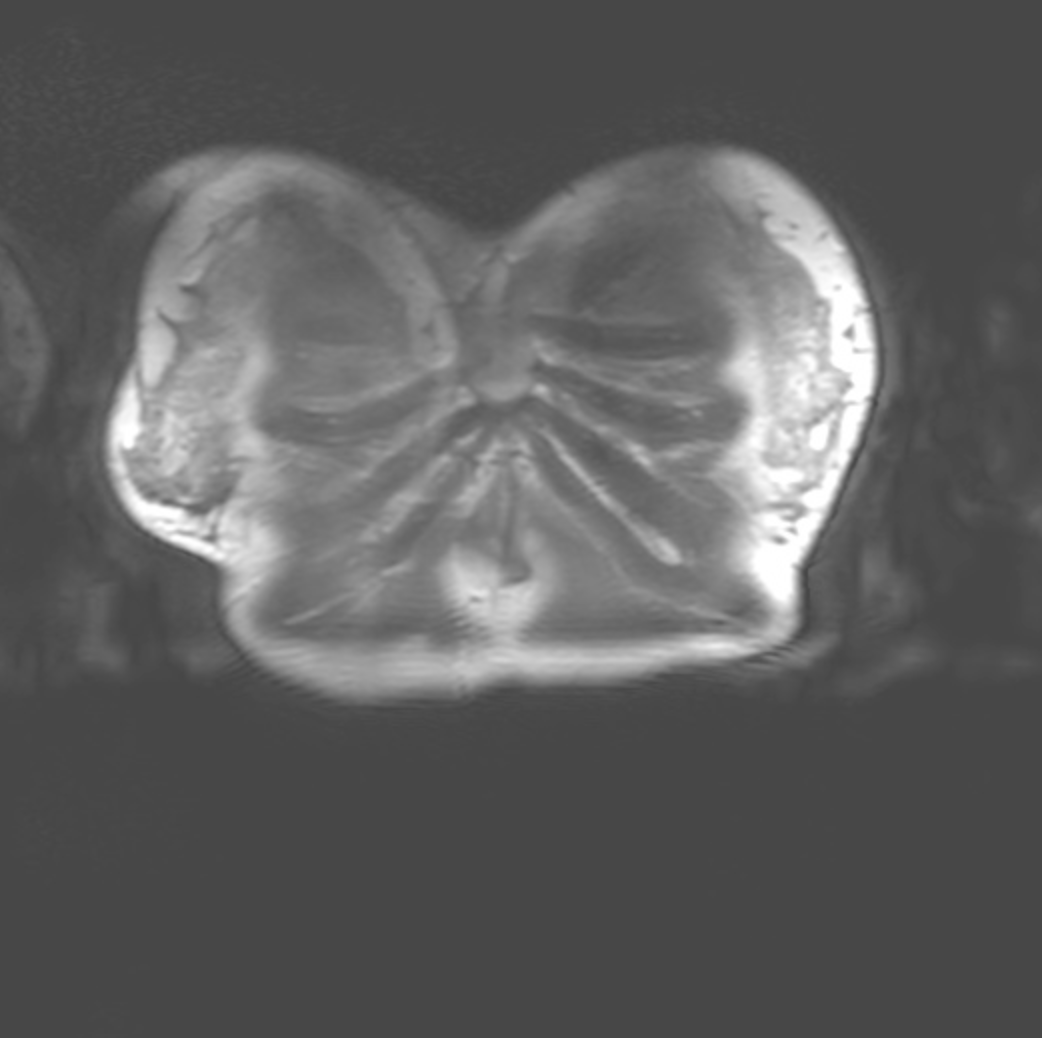

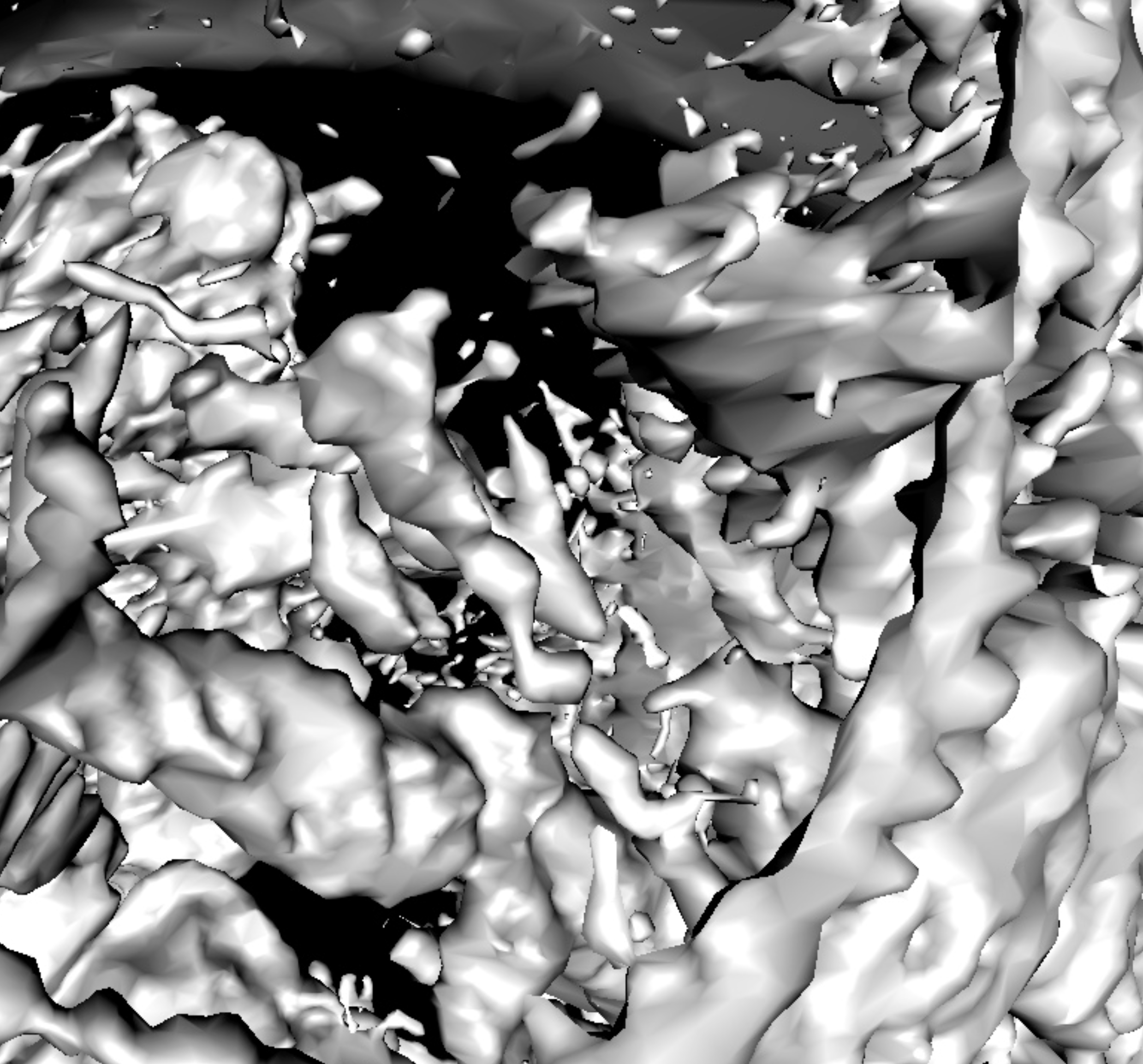

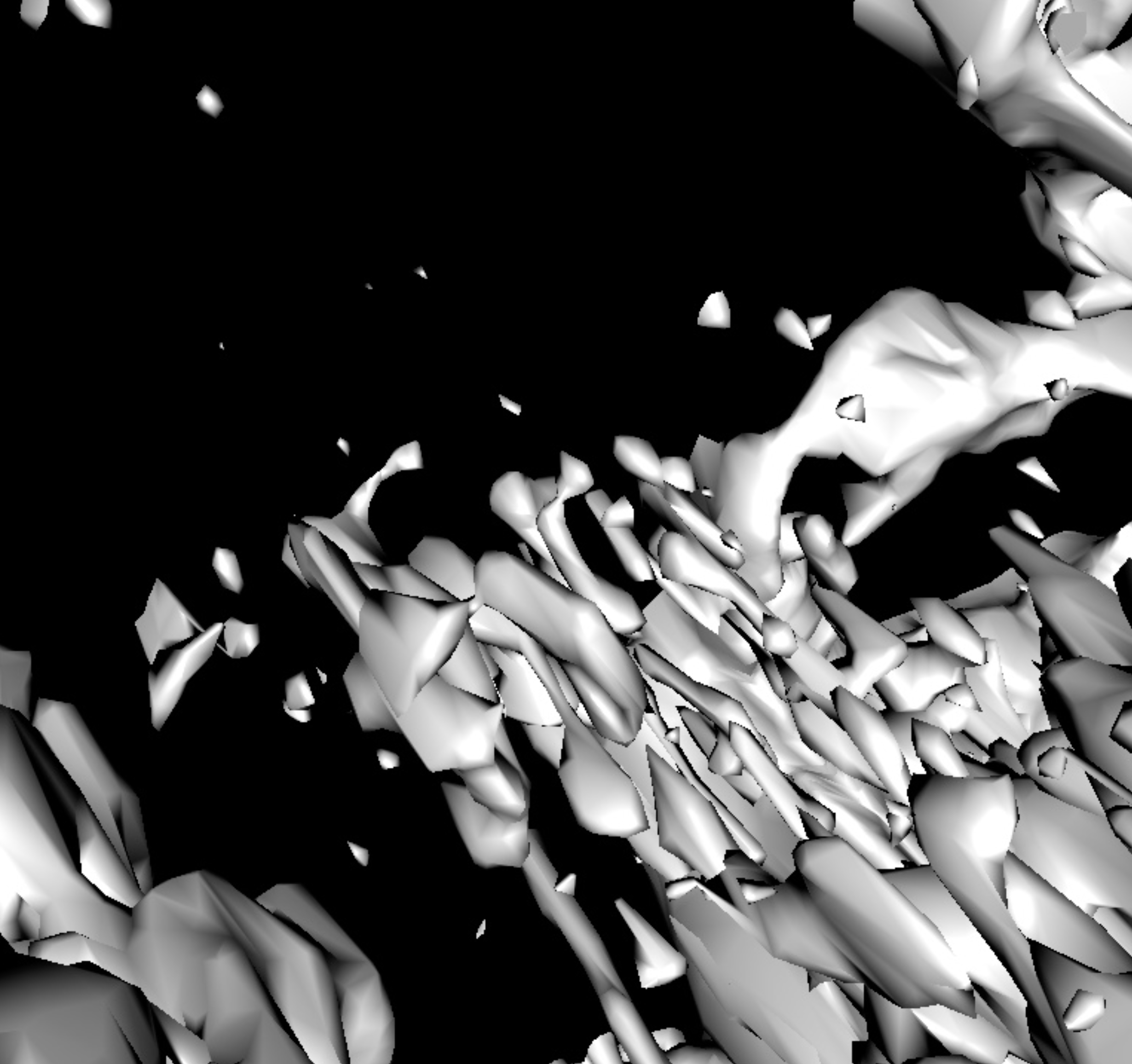

001cI created a true-to-scale sculpture of my MRI data: a materialisation of un-tangible bodily data. This data was taking in medical trials in 2018 - a year beforeI was diagnosed with breast cancer. Milled from dense fleshy pink foam, this sculpture is a physical and tactile rendering of what MRI reveals. The changes I made to my data resulted in patchy and globular, partial and flayed forms. I created an animated ‘fly through’ of this data. Stills from this data can be seen above. My data sculpture is an uncertain embodiment of subjectivity contextualised by the speculative, unknown status of my cancer in 2018. The danger which my data sculpture may or may not contain is emotionally untranslatable.

My MRI images and data sculpture tethered my phantoms to my bodily matter which is always in flux and always hybrid, subject to ongoing evolution and random mutation. This is what makes bodily matter unfathomable. Disrupting and fragmenting essentialist and totalising social categories is central to queer theory, definitions of the abject, and disability studies and was a parallel between my practice and my experience of cancer (Cox, 2018). Critical factors that influenced how and what materials I would use to make my phantoms depended on matter that was organic or a ‘tissue mimicking material’ (TMM). I also drew from the experience of working with my data by allowing globular forms to emerge through how I made my phantoms. Kristeva (1982) analyses different abject subjects, demarking their commonality in power to disrupt or threaten notions of a whole self. My data sculpture displaces bodily boundaries and disfigures bodily forms. My data sculpture was made before my cancer diagnosis. The affecting psychological response this stirs in me when I hold the data sculpture in my arms illustrates the type of agency inanimate objects can possess. I wanted to harness and nurture this affective power. My data sculpture produced a necessary and troubling reforging of my data via my gaze. No longer a diagnostically readable image, my data sculpture distorts the symbolic and normative discourse of MRI images. Being simultaneously “too alien and too close” my data sculpture informs how I create my phantom organs (Bennett, 2010, pp. 3-4).